Daniele da Volterra’s The Descent from the Cross – a faded shadow of a great work, meaning the aftermath of vandalism

The painting, which is the subject of our interest is presently located in the second (on the left) chapel of the Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti. At the moment of its creation, it was, however, located elsewhere. Its fate is a testimony to the fragility of art. It shows, how it can be completely destroyed and not as a result of the ravages of war, but…in the name of adoration.

However, our story should begin with the circumstances of the work’s creation. The famous condottierii Niccolò Orsini di Pitigliano had died in 1510. He was the representative of one of the oldest Italian aristocratic families, whose history dates back to the Middle Ages. His son Aldobrandini Orsini – the archbishop of Nicosia, but also the canon of St. Peter’s Basilica had six (biological) children, whom the grandfather did not intend to acknowledge. After his death, however, the archbishop decided to legitimize his offspring and give them the legal right of inheritance but also his surname. As we can imagine not everyone was pleased, and most certainly the siblings of the archbishop were none too happy. The procreation of children and even caring for them did not justify bestowing a surname upon them. Aldobrandini who was oblivious to this disapproval continued his efforts working on a family compromise and at the same time searching for an appropriate burial site. With that in mind, he bought a chapel (the fourth on the right side from the nave) in the Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti and began the process of its decoration, but in 1527 he died. The works on the chapel were interrupted by the Sacco di Roma, and later they went on for a long time, until finally the only daughter of the archbishop, Elena Orsini took matters into her own hands.

Initially, she continued the plans of her father. The chapel was to commemorate two saints: Francis of Paola and Jerome. A few years later, Elena changed her mind. She decided to give it a new dedication, create unprecedented decorations, and as a result create a place that would be a testimony to her deep faith and patronage worthy of the great surname which she bore. The chapel was to amaze and move, and the art was to be the main tool in accomplishing this goal. Elena prepared the iconographic program, chose the sources necessary to create the appropriate narration, and then actively supported the artist whom she had chosen. In 1541 she signed a contract with Daniele da Volterra, obliging him to complete frescoes on the walls and ceiling of the chapel, as well as stuccos which would provide the appropriate frames for the figural representations. Per the wishes of the founder, they were to tell the story of her namesake Helen and intertwine with the story of the Crucifix connected with her. The figure of Helen fit perfectly with the ambitions and desires of Elena Orsini, who often encountered ostracism due to the surname which she received against the wishes of the family’s senior. The mother of Emperor Constantine – a woman of deep faith and great compassion shown to the weak and the infirm, despite her low origins became a venerated empress and then a saint. The religious and devoted to charity Elena Orsini found in her, her spiritual guide and patron.

The fresco The Descent from the Cross, which was the beginning of this story, occupied the front wall of the chapel and was decorated with a wide frame made of stucco. Thanks to this a very novel and decorative effect was achieved – the fresco looked like a painting, which was supported by two muscular caryatids facing each other. They seemed to be made of marble, although in reality they were painted. Similar caryatids also appeared in the two side walls of the chapel decorated with the scenes: The Finding of the True Cross and The Emperor Heraclius Carries the Cross to Jerusalem.

In the fresco depicting the descent from the Cross, the painter created a multi-figure composition (15 figures), which is concentrated around two scenes – in the center of one of these is the body of Christ supported by men, the other is a group of women concentrating around the unconscious Mary. The men are occupied with the dead body, the women with its mourning, however in an indirect way. Daniele da Volterra does not show the despair of women over the body of the Savior, but rather their sadness over the mother who has fainted with grief. If that was not enough the three Marys gathered around her (Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of Clopas, and Mary Salome) seem not to notice the main scene of the fresco. Another surprise is the placement of Our Lady's body, reminiscent of that, which in the representation of the Pieta is generally reserved for Jesus. In this way, the artist showed us the tragedy of the mother, which seems to be comparable with the death of her son. Men's hands as the rays of the sun surround Jesus pointing to him and seemingly informing that this is the main scene, however, our eyes are still unknowingly directed towards the four Marys.

Let us take a look at the exceptionally set out vertical perspective, which is constructed by the cross and ladders. The descending corpse of Christ, shown in a strong foreshortening, imitates the depth of the painting providing it with three-dimensionality. The three highest-placed men seem to be soaring around Christ, free of gravity and whipped with gusts of strong wind, while their loincloths and cloaks theatrically blow about. The lower part of the painting, the most trembling and dynamic, attracts attention with its rich draping of the women's robes, thus showing their internal struggle constituting a counterbalance for the dead, monumental figure of Jesus.

The muscular, half-nude manly bodies suggest an inspiration with the work of Michelangelo, who had just finished his Last Judgement (1541) in the Sistine Chapel. Still today, historians are debating whether the idea of this composition did not come from the mind of this genius, or at least was largely his doing, which happened more than once. Michelangelo gave advice, but also supported da Volterra by supplying him with sketches and drawings.

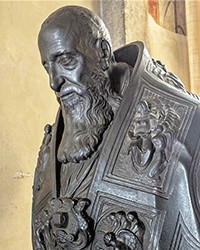

As we can see the challenge which was undertaken by da Volterra was significant indeed. According to Vasari, who was his friend and chronicler, he worked on it for seven years and felt exhausted towards the end. We know, that at that time the artist also accepted other commissions, which resulted in the stoppage and delay of works on the Orsini Chapel. They were finally completed between 1545 and 1548, and for the artist became a ticket to significant commissions at the court of Pope Paul III. Da Volterra became famous and appreciated and in time he was considered to be the student and continuator of Michelangelo.

The Orsini Chapel aroused admiration in his contemporaries and had to appeal to its founder. Throngs of artists and tourists came to see it. As it would turn out the fame of this place also contributed to its tragedy. During the occupation of Rome by the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte, his people who occupied themselves with stealing the most magnificent works of art did not forget the famous Descent from the Cross. However, the main problem was the technique – a fresco is not easy to pack and take to the Louvre, as was the case with numerous paintings and sculptures which were stolen by the occupants. In 1800 the French started demolishing the chapel. They started with the side wall in order to get to the fresco on the front. However, the cuts were so deep that they damaged the construction of the whole. The vault depicting the episodes of Helen’s search for the Cross collapsed, while the chapel itself was exposed to rain and wind. The frescoes of the side walls were also irrecoverably lost. We are familiar with them, to a large extent, thanks to da Volterra's drawings spread all over Europe. The Descent from the Cross, which remained in the chapel, deteriorated in the following years, until 1809 when Pietro Palmaroli came up with the idea of taking the fresco off the plasterwork and transferring it onto canvas. This painter and conservator, but also a well-known art merchant in Europe, in subsequent years, subjected the painting to a long-lasting process of transferring it onto the canvas with the aid of heating with glue several subsequent layers of the thin canvas with the aim of separating the last (thinnest) layer of the fresco from the wall. Then in the same way with the use of water, he separated the remaining (on the other side) plasterwork, thus obtaining canvas which was relatively thin, however, which lost in intensity and shine of the original paints. Then the painting underwent corrections and reconstructions so that by the end it looked like a shining with varnish oil painting. Was this the reason that the French disappointed with the results decided to abandon it? Perhaps a feeling of shame which they felt in connection with this neither painting, neither fresco, reminded them of the ruin of the magnificent chapel, which they caused.

In 1816 da Volterra’s The Descent from the Cross finally returned to the church, but not to the devastated Orsini Chapel, but rather to the Bonfili Chapel in which it can be viewed without frames and painting decorations, but most of all without the context, which Elena Orsini had wanted. Today we can only read about the reactions of those who had seen the original fresco and praised its lively colors and exceptional chiaroscuro. The work had lost a lot, but it still convincingly presents the gamma of human feelings and the strength of expression, testifying of the exceptional talent of its creator.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !